This information has been commissioned by the Goulburn Murray Valley (GMV) Fruit Fly Program and is funded by the Victorian Government. Use of this material in its complete and original format, acknowledging its source, is permitted, however unauthorised alterations to the text or content is not permitted.

Current fruit fly activity

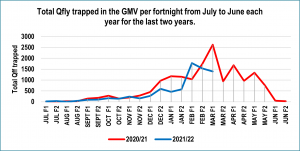

Total numbers of Queensland fruit fly (Qfly) trapped in the Goulburn Murray Valley (GMV) peaked during weeks 1 and 2 of February 2022 with 1,775 flies trapped (Fig. 1). This was a significant increase over the data for weeks 3 and 4 of January where there were 567 flies trapped. Since the peak, up to 15 March, the count has dropped to 1,391 flies.

The numbers of Qfly trapped in the region will decline as autumn sets in. Fruit fly activity will proceed however, despite lower numbers being trapped. This is because temperatures will become too cold for trapping but will not be cold enough to stop mating, egg-laying and larval development – at least in the first half of autumn (see Fig. 6 for a description of fruit fly activity throughout a typical fruit fly season).

Now is the season for fruit flies to build up before the cold hits and if they survive the winter will start a new season of fruit damage next spring. This is where orchard (or post-harvest) hygiene becomes important. You will break the fruit fly cycle by successfully cleaning up your orchard, home garden and nearby untended land of potential fruit fly host material: No fruit = No fruit fly.

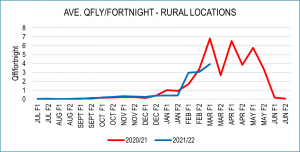

Current fruit fly activity compared with past years

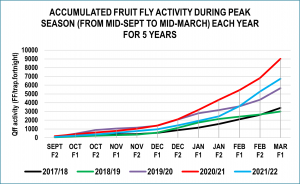

The 2021/22 fruit fly season started off as less severe than last season (2020/21) (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). There was a quick rise in fruit fly numbers from about the second half of January but, even so, numbers are down compared with last season. If autumn fruit flies can be managed successfully then fly numbers for next season will also be down and so will be more easily managed next spring.

Fig 1

Fig 2

Fruit fly activity in rural Vs urban locations

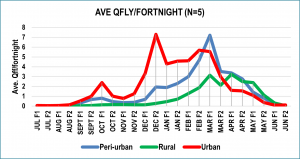

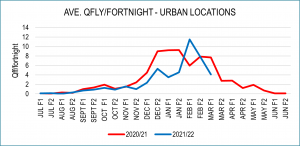

In most years during March there is a cross-over of fruit fly populations from urban areas into rural areas (Fig. 3). This aligns with fruit becoming scarcer in urban areas as it is harvested or eaten by birds and becoming more plentiful in rural areas of the GMV as large-scale pome and stone fruit crops ripen. This phenomenon is occurring again this year (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5).

Even though numbers in urban areas may be down this does not mean that all fruit flies have left urban areas. Many adults may have moved on, but they will have left their offspring in urban areas in the form of eggs, larvae and pupae in and around late-infested fruit that hasn’t been picked up and destroyed. These will form adults towards the end of April when it’s too cold to be attracted to traps and will overwinter in warm spots on the urban landscape so that they are ready to infest fruit in the new season next spring. Removing these infestation sources before flies can find them will break the fruit fly cycle and reduce the number of adults surviving into next spring.

Fig 3

Fig 4

Fig 5

Locations with high fruit fly activity

Table 1 lists GMV fruit fly trapping locations and numbers of sites in each location where greater than or equal to 20 Qfly were trapped in the three-week period to 18 March 2022. This figure (i.e. ³20 Qfly in 3 weeks) indicates dangerously high Qfly populations which should be managed before they become a serious problem in current and future crops.

It is recommended that:

- Home gardeners in these locations be aware of the presence of fruit flies in their area and carry out fruit fly management strategies including:

- The use of netting or bagging

- Fruit or plant removal

- Fruit examination (for eggs and larvae)

- Notifying authorities of nearby untended/ feral fruiting plants

- Commercial growers in or near these locations should also be aware of fruit flies being nearby and implement fruit fly control:

- Monitor fruit fly traps for Qfly population presence and build-up

- Check fruit for fruit fly infestation

- Weekly baiting

- If the fruit fly problem is too severe, use approved pesticides

- Carry out after harvest clean-up

- Keep house gardens clean, too as well as creek banks, compost heaps, roadsides

- Notifying authorities of nearby untended/ feral fruiting plants

- Ensure stock of traps, lures, toxicants, approved pesticides, baits, application equipment, etc are in good supply and good condition.

Table 1

Impact of past weather patterns on fruit fly activity

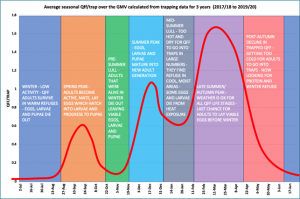

Fruit fly trapping data have been collected throughout the GMV for at least 5 fruit fly seasons (from 1 July to 30 June). Fruit fly activity, based on the numbers of trapped fruit flies, varies throughout the year (Fig. 6). March is most often the month where most fruit flies are trapped and these trappings correspond with the ripening of large volumes of pome and stone fruit in commercial orchards. It also corresponds with the most benign weather conditions for fruit fly survival and proliferation.

Flies emerging from fruit infested at this time of year (emergence of these flies will be in early April) typically are not attracted to traps due to the cool weather in April. It will seem that flies are in decline but that’s not necessarily the case. These flies will ‘hibernate’ over winter as adults. The greater the numbers of these flies overwintering the greater the problem will be in spring and next cropping season if not managed adequately.

Fig 6

Table 2 and Table 3 compare daily mean temperatures ([max+min]/2) averaged over a fortnight and fortnightly total rainfall recorded at Cobram Post Office for the last 5 fruit fly seasons. They show that temperatures in early 2021/22 were slower to rise than in previous years (early October to mid-December). This caused a delay in fruit fly population build-up in late 2021. With the exception of early February 2022 rainfall has been higher in 2021/22 than most other years. That and corresponding higher humidity and lower desiccation meant that there was negligible adverse climatic impact on fruit flies and the fruit they infested in December and January. The high rainfall in March 2022 will exacerbate the fruit fly problem.

Table 2

Table 3

Weather outlook

Information provided by the Bureau of Meteorology:

Rainfall: A 60% to 65% chance that rainfall will exceed the average of 25mm to 50mm during April.

- NO ADVERSE OR BENEFICIAL IMPACT ON FRUIT FLY SURVIVAL

Maximum temperature: A 55% to 65% chance that maximum temperatures will exceed the average of 24˚C to 27˚C in April. This increase will only be in the order of a 1˚C increase.

- SLIGHT BENEFICIAL EFFECT ON FRUIT FLY SURVIVAL

Minimum temperature: A 65% TO 75% chance of minimum temperatures exceeding the average of 6˚C to 12˚C for April. This increase is likely to be about 2˚C.

- BENEFICIAL EFFECT ON FRUIT FLY SURVIVAL

Normally, fruit fly activity declines in late April so that any eggs or larvae in fruit or pupae in the ground in the GMV past mid-April will die due to the cold.

But – forecast weather conditions for April 2022 will not be damaging to fruit fly survival and activity. They suggest that the fruit fly season will extend further into autumn than usual. Fruit fly activity in the form of mating, egg-laying and consequent fruit damage followed by adult emergence will remain significant possibly into May if the weather does not turn cold quickly.

Goulburn Murray Valley Fruit Fly Program

For assistance in managing Qfly, contact the Project Coordinator at the GMV Fruit Fly Office by phoning (03) 5871 9222 or email gmvfruitfly@moira.vic.gov.au. For more information on fruit fly control and area wide management strategies visit www.fruitflycontrol.com.au

This report was produced and supplied by Janren Consulting Pty Ltd for the purpose of the GMV Fruit Fly Program. The GMV Fruit Fly Program is supported by the Victorian Government.