This information has been commissioned by the Goulburn Murray Valley Area Wide Management Fruit Fly Program and is funded by the Victorian Government. Use of this material in its complete and original format, acknowledging its source, is permitted, however unauthorised alterations to the text or content is not permitted.

Fruit fly snapshot

- A La Niña event has impacted the timing of the initial spring peak for the third year in a row. Generally, Queensland Fruit Fly populations in the Goulburn Murray Valley (GMV) start to expand in September but, due to the cooler temperatures and higher rainfalls the spring peak commenced in late October/ early November each year for the past three years.

- At present (first fortnight of January 2023) 49% and of the region’s Queensland Fruit Fly population is located in urban sites whereas the second week of December 2022 the ratio was higher (62%). This suggests that fruit fly have commenced their migration from urban to rural locations using peri-urban host fruit as steppingstones.

- Currently, weather conditions are suitable for Queensland Fruit Fly to mate and lay eggs although hot, dry weather, in some areas, will reduce the numbers of fruit available for fruit fly to sting.

- The heat will kill eggs and larvae in fallen fruit that is exposed to the sun.

- Eggs laid during January, if they survive the GMV’s usual heat and lack of moisture (which is likely, under current La Niña conditions), will become a new generation of pest fruit flies in late summer and autumn which will attack your autumn crop of fruit and fruiting vegetables.

- Ripe or ripening fruit present during February, especially those under irrigation, are particularly susceptible to Queensland Fruit Fly stinging fruit.

- These flies may spread from urban areas, through peri-urban sites and into commercial crops during this time.

- Action now will cut the next generation and increase future home garden productivity –

- Fruit and tree removal and destruction, fruit fly baits, netting, and monitoring ripening fruit for sting marks or with traps in home gardens, untended areas, such as council and Crown land, roadsides, riverbanks and business sites.

- Action for commercial orchardists include:

- Ensure fresh (or within use-by date) traps are deployed and are being checked as often as possible – certainly once a week.

- Check ripe and ripening fruit for fruit fly sting marks – preferably daily.

- If Queensland Fruit Fly is a constant problem, ensure supplies of fruit fly control material such as baits and approved pesticides are in storage and within their use-by dates.

General population trends

A total of 3,501 Queensland Fruit Fly were trapped from approximately 350 traps so far this fruit fly season (starting from early July 2022) [Table 1]. This is slightly more than for the same period last year (2,994) and fewer than 2020/21 (5,560).

The 2020/21 fruit fly season was a heavy year for Queensland Fruit Fly. This was most likely due to a combination of benign weather conditions during the previous autumn, winter and spring (i.e. a La Niña event); plus a large volume of unharvested host crop due to COVID restrictions. It is believed that the combination of the GMV’s area-wide management program and periodic weather conditions that impacted adversely on Queensland Fruit Fly survival during last season (2021/22) and the current season (2022/23).

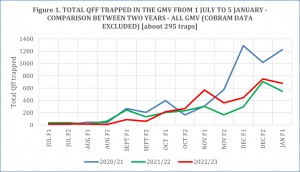

Figure 1 and Table 1 show that there has been a decline in numbers of Queensland Fruit Fly trapped during late spring and early summer compared with two years ago. Trends in 2021/22 and 2022/23 were similar.

NOTE: F1 = weeks 1 and 2; F2 = weeks 3 and 4 for each month

Table 1. Total Queensland Fruit Fly trapped in the GMV from 1 July to 15 January, each year from 2020.

| Season (1 Jul – 15 Jan) | Total Qff trapped |

| 2020/21 | 5560 |

| 2021/22 | 2994 |

| 2022/23 | 3501 |

Impact of Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) pilot trial in Cobram

A Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) pilot trial was carried out in Cobram from September 2019 to May 2022. SIT is a biological control method where large numbers of Queensland Fruit Fly are raised in a laboratory in South Australia, sterilised using x-rays and released. These sterile flies mate with wild Queensland Fruit Fly who then produce zero fertile offspring causing a decline and eventual extinction of Queensland Fruit Fly.

The pilot trial in Cobram had almost immediate effect on local Queensland Fruit Fly populations. Table 2 shows that during pre-SIT seasons (1 July to 15 January for 2017/18 and 2018/19) Queensland Fruit Fly trapped in Cobram accounted for relatively high levels compared with the rest of the GMV. SIT resulted in a very significant reduction in this percentage. Now that SIT has ceased in Cobram the percentage of Queensland Fruit Fly coming from Cobram has increased. Nearly one half (45%) of all GMV’s Queensland Fruit Fly trapped from 1 July 2022 to 15 January 2023 came from Cobram. This means that GMV’s Queensland Fruit Fly data are now heavily leveraged by Cobram’s Queensland Fruit Fly.

Table 2. Total Queensland Fruit Fly trapped in the GMV from 1 July to 15 January, each year from 2020.

| Season (1 Jul – 15 Jan) | SIT status | % of total regional Qff trapped in Cobram |

| 2017/18 | Pre-SIT | 37 |

| 2018/19 | Pre-SIT | 25 |

| 2019/20 | SIT | 5 |

| 2020/21 | SIT | 6 |

| 2021/22 | SIT | 14 |

| 2022/23 | Post-SIT | 45 |

Impact of land use type

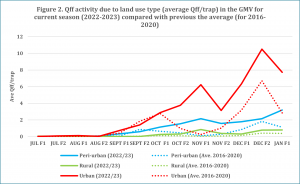

This year the general trend in Queensland Fruit Fly numbers is following the usual trend (see Figure 2) according to the type of land use surrounding Queensland Fruit Fly trap sites. Numbers being trapped are now on the rise in peri-urban and rural areas but are declining in urban areas.

Rural traps caught 767 Queensland Fruit Fly (22%) during this period while the majority (1,937; 55%) were trapped in urban locations. Peri-urban traps caught 23% of Queensland Fruit Fly in the GMV during this period [Table 3]. Numbers of Queensland Fruit Fly trapped were a little higher this year than last year for rural, peri-urban and urban locations but lower than the previous year (2020/21) for all land use categories.

NOTE: F1 = weeks 1 and 2; F2 = weeks 3 and 4 for each month

Table 3. Comparison of Queensland Fruit Fly trapping data over three years (each year from 1 July to 15 January) divided into different land use types (Cobram data excluded) [about 350 traps].

| Land use type | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | |||

| Total Qff | % of total | Total Qff | % of total | Total Qff | % of total | |

| Peri-urban | 1024 | 18 | 580 | 19 | 797 | 23 |

| Rural | 1177 | 21 | 744 | 25 | 767 | 22 |

| Urban | 3359 | 61 | 1670 | 56 | 1937 | 55 |

| Total | 5560 | 2994 | 3491 | |||

Queensland Fruit Fly outlook for home gardeners in the GMV

Typically, at this time of year fruiting plants are finishing off in urban areas of the GMV as fruit is harvested, eaten by birds or deteriorate and fall off due to hot, dry weather. As a result, Queensland Fruit Fly populations generally decline during January and February in urban areas across the region.

The Bureau of Meteorology forecasts similar rainfall (i.e. low or possibly a slight increase due to La Niña impacts) and minimum temperatures to the average but maximum temperatures are likely to be slightly lower than average. These weather patterns favour the survival of both fruit on tree/vine/bush and fruit fly.

All of the above observations change when garden irrigation is used in urban areas. Irrigation provides ideal conditions for Queensland Fruit Fly maturation, survival and proliferation. Fruit fly populations can explode and then, when crops in urban locations are diminished Queensland Fruit Fly move out of urban areas, into and through peri-urban places and into commercial orchards. This migration is facilitated by high volumes of fruit in commercial orchards ripening from February through May.

If urban growers can deal with Queensland Fruit Fly in their gardens using the usual area-wide management strategies described, they will achieve better production in their own garden and also assist commercial growers by cutting off the urban-to-rural migration of Queensland Fruit Fly.

Queensland Fruit Fly outlook for commercial horticultural production in the GMV

Queensland Fruit Fly start to build up in peri-urban and rural locations of the GMV during February. Many Queensland Fruit Fly move out of urban areas and into rural locations due to lack of resources, irrigation in rural areas and mass-ripening of fresh fruit. However, some Queensland Fruit Fly may have overwintered in rural locations within evergreen canopies often in sites close to houses and other heated out-buildings. These flies will start moving out of hibernation and start looking for mates and fresh ripening fruit to infest.

It is essential for commercial growers to ensure there are no unwanted fruiting plants within about 1km of their orchard: roadside feral fruits (e.g. peaches), plants along creek banks, on Crown land, abandoned orchards and, very importantly, the house yards of your orchard and the neighbours. These fruit are the staging points for a rapid increase in populations that then threaten crops.

Commercial orchards situated within 1km of high population centres mentioned below are especially at risk from Queensland Fruit Fly. Vigilance with traps and by fruit checking is essential in these areas.

Sites with high Queensland Fruit Fly populations

Throughout the GMV, with approximately 350 traps, there is a general trend of a similar to slightly higher Queensland Fruit Fly count this season compared with last season but much lower than the 2020/21 season. However, there are a few locations that heavily bias total numbers. These are sites with high populations of Queensland Fruit Fly. These sites can be habitual, where high populations occur each year at approximately the same time or may be ‘new’ high population sites where fruit fly have moved into a new area, settled there and proliferated.

Active area-wide management works, especially netting and host plant removal (in urban areas), baiting (in commercial production areas), trap monitoring and fruit checking (in all areas of the GMV) will, over time, erase these high populations.

At present most high population sites are located in urban areas.

Table 4. Locations with trapping sites registering 12 or more Queensland Fruit Fly in total over the last four weeks.

| COBRAM |

| KYABRAM |

| MERRIGUM |

| MOOROOPNA |

| SHEPPARTON |

| TATURA |

| UNDERA |

The abovementioned sites are of concern as they could become sites from which large numbers of Queensland Fruit Fly could establish and then spread, so it is important that members of the community who have gardens and orchards in these areas take precautions to reduce the ability of fruit fly to infest fruit and survive in them.

Weather outlook and its impact on Queensland Fruit Fly

Over the next few weeks, the numbers of Queensland Fruit Fly trapped in the GMV, if they follow normal trends, will rise. This will be the commencement of the peak fruit fly season which will then spread, if left untouched, from urban areas to commercial orchards in the local district.

Weather forecasts for February 2023 were accessed from the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) website (http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/outlooks) on 30 January 2023. Data indicate that:

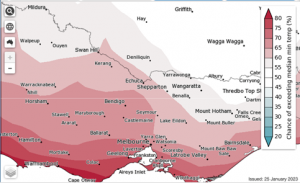

- There is a 50% chance that rainfall over the GMV will exceed the average (which is predominantly 5-10mm for February based on the past 10 years). Despite this, more rain than normal may fall because it is expected that La Niña may persist into February.

- There is a 50% chance that maximum temperatures will be higher than the average of 30-33°C. Persisting La Niña effects are not likely to cause higher maximum temperatures.

- There is a 55-60% chance that minimum temperatures will be above average of 12°C to 18°C. La Niña is likely to push up minimum temperatures a little.

Usual January/ February weather patterns are hot and dry. The BOM’s forecasts suggests that February conditions will not be greatly different from normal although, if La Niña persists through February, temperature conditions may be a little milder than usual – but only by 1˚C or less. Although the forecast temperatures are optimal for fruit fly survival and development rainfall is a limiting factor. Even if there is more rain than average it is still lower than optimal for Queensland Fruit Fly. However, in home gardens where weather conditions are modified by irrigation, and the presence of evergreen plants for refuge and early fruits and vegetables for egg-laying, Queensland Fruit Fly will thrive if not managed correctly. During this period of the year many Queensland Fruit Fly will likely migrate from home gardens, through peri-urban orchards and gardens and into outlying rural commercial orchards and gardens.

Figure 3. Chance of exceeding median rainfall in February 2023

Figure 4. Maximum temperatures: Chance of exceeding median for February 2023

Figure 5: Minimum temperatures: Chance of exceeding median for February 2023

Goulburn Murray Valley Area Wide Management Fruit Fly Program

For assistance in managing fruit fly, contact the Project Coordinator at the Goulburn Murray Valley Fruit Fly Office by phoning (03) 5871 9222 or email gmvfruitfly@moira.vic.gov.au. For more information on fruit fly control and area wide management strategies scan the QR code below.

This report was produced and supplied by Janren Consulting Pty Ltd for the purpose of the Goulburn Murray Valley Fruit Fly Program. The Goulburn Murray Valley Fruit Fly Area Wide Management Program is supported by the Victorian Government.